| P&W 160-series "Strafford" Cars | ||

|

||

|

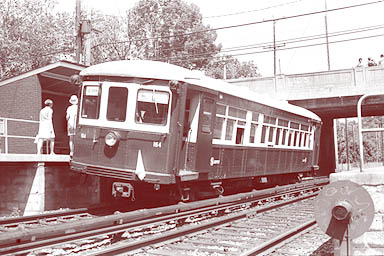

1927-built no. 164 in special service, carrying

spectators to the June 1981 U.S. Open at Merion

Golf Club. |

| The "Strafford" Cars of

the Philadelphia and Western Railway Click here for Matt's up-to-date roster of the Strafford Cars The Philadelphia and Western Railway was originally envisioned as the eastern connection of a transcontinental railway being assembled by financier Jay Gould shortly after the turn of the 20th century. The railway was never constructed to the extent that was envisioned, however, opening as an electric interurban railway in 1907 from 69th Street Terminal in Upper Darby, approximately 1/2 west of the Philadelphia city line, to Strafford, a wealthy suburban town located along the Pennsylvania Railroad's mainline. The line was not constructed with overhead wire for electric propulsion, as most interurban lines, but instead used an outside third rail. The line opened with a fleet of 22 wooden interurban cars built by the St. Louis Car Company. In 1912, the Philadelphia and Western constructed a branch from Villanova to Norristown, Pennsylvania, where it connected with the Lehigh Valley Transit Company's "Liberty Bell Route" to Allentown, Pennsylvania. The company did not use overhead wire for electric propulsion, but instead used an outside third rail. The original wooden cars of the P&W, as the railway became known, provided all service over both branches until 1920, when a single new car type was delivered. This car, #50, was followed by two nearly identical cars 2 years later. The cars did not have the required steps floor traps necessitated by the street level platform in Norristown, and thus were confined to runs over the Strafford branch as well as rush-hour local trips. They were not exactly what the P&W was looking for to replace their wooden car fleet, but were the first all-steel cars owned by the railway. The P&W ordered a sample car, car #60, in 1924 from the J.G. Brill company of Philadelphia. This car was similar to the three 50 series cars but had several differences. It was several feet shorter, several inches narrower, and had the required steps and poles so it could be used on the branch to Norristown. Maximum speed was 44 miles per hour, and the cars featured smoking compartments, parcel racks, and train doors for easier passage between trains of more than one car. The P&W was pleased with car #60, and subsequently ordered 5 more cars (#'s 61-65) in 1927 from J.G. Brill in order #22529, followed in 1929 by 5 additional cars (#'s 66-70) in J.G. Brill order #22773, bring the total fleet of 60 cars to 11 by 1929. The stock market crash of 1929 had a severe impact on the P&W. The company was competing with electrified suburban trains directly from downtown Philadelphia of the Pennsylvania Railroad at Strafford, and both the Pennsylvania and Reading Railroads at Norristown. In order to woo riders away from the railroad companies and onto to the P&W's interurban cars, new president Dr. Thomas Conway sought to convert the struggling interurban into a high-speed interurban railway, offering fast service with the most state of the art equipment available. Following a year of research and development, the P&W began operation of 10 high-speed "Bullet" cars constructed by J.G. Brill in 1931. The Bullets were constructed of aluminum alloys and could attain speeds in excess of 80 miles per hour. The P&W track structure and station platforms were reconstructed to allow high speed operation and a subsequent reduction of travel times was introduced along with the new Bullet cars. Part of the modernization of the P&W involved a careful study of its rolling stock. The Bullets were purchased to provide high-speed service to Norristown, but the company faced a dilemma in that the 60 series cars, the last 5 of which were a mere 2 years old, really did not fit in the modernization plans. The cars were slow, with a top speed of only 44 miles per hour, and the cars rode rather high over their trucks, thus not well suited to the new, lower station platforms constructed for the Bullet cars. They were cleared not suited to the high-speed operation planned for the future of the P&W. Rather than scrap these nearly new 11 cars, the P&W began a substantial rebuilding program for these cars. The doors at each end were removed, as were the side doors located at the division between the smoking and non-smoking sections. Trolley poles were removed, along with the ground level steps and traps, as the new Norristown terminal had high level platforms and trolley poles were no longer necessary. The car floors were lowered through a reconstruction of the car bolsters and use of smaller wheel on the car trucks. This, in turn, created a lower center of gravity for the cars and greatly improved riding qualities. The car interiors were completely reconfigured, with smoking sections removed, wider seats were installed, and parcel racks were removed. Perhaps most importantly, motors were rewound, which along with the lowering of the cars' center of gravity increased their maximum speed to 68 miles per hour. The cars were rebuilt in stages, with eight cars rebuilt in 1931, and the remaining three cars rebuilt in 1935. The new cars held down all base service assignments on the Strafford branch and were commonly used in Bryn Mawr, Villanova, and Wynnewood Road local service. The rebuilt cars helped decrease running times on the Strafford branch by 5 minutes. The 50 series cars were relegated to local service after the rebuilt 160 cars took over Strafford service in 1931. The Strafford cars found heavy use during boom times for the P&W and the surrounding western suburbs of Philadelphia during and immediately after World War II. Two car trains were occasionally run during heavy rush hours and two and three car trains of Strafford cars were a common sight on railfan excursions from the 1940s through the 1970s. The P&W itself was purchased by the neighboring Philadelphia Suburban Transportation (PST) Company, commonly known as the Red Arrow Lines, in 1954. Shortly after the PST purchased the P&W, the three 50 series cars were retired from service and cut up for scrap in 1955. During the 1960s and 1970s the Strafford cars continued to be used primarily for rush hour services and provided most base services during snow emergencies due to their heavy weight. Starting in the 1960s, the upper window sash of the cars was modified and paired the upper sash of adjoining windows. The first Strafford car to be retired was #169, which was destroyed in a heater fire at 69th Street Terminal in 1960. This was the first car of the fleet scrapped. In 1969, car #170 was destroyed in a collision with Liberty Liner "Independence Hall", and was scrapped in 1970. This car had been painted, briefly, in an experimental paint scheme after the PST takeover in 1954. Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, commonly known as SEPTA, purchased the PST in 1970. Shortly after the SEPTA takeover, car #165 was painted in an experimental tan color scheme, a scheme that only lasted a few weeks. The next SEPTA paint scheme was an orange color scheme applied to cars #160 and #161 at least. Several other cars in the fleet, however, continued to be painted in the traditional red and cream color scheme. SEPTA also began to replace the front windows with safety glass mounted in rubber frames during the 1970s. During the 1980s, SEPTA began to repaint the remaining cars in its new system-wide color scheme of red, white, and blue. Cars that were painted in this scheme were #'s 161, 163, 164, 165, 167, and 168. Car #160 was destroyed in a tragic collision with Bullet car #200 in 1985 after #200 was derailed by vandals. The following year, car #166 was damaged by fire at 69th Street Terminal and retired. The fleet continued to dwindle as car #167 was destroyed after it crashed into the platform at the 69th Street Terminal in August 1986. Following this wreck, the line was shut down for several weeks. So many Strafford and Bullet cars had been retired that SEPTA had to purchase used elevated cars from the Chicago Transit Authority before reopening the line. Following car #167's wreck, car #'s 164, 165, and 168 were retired from service and stored. Car #164 was later rebuilt into a work car and was used to de-ice the third rail during winter storms for several years. The final three Strafford cars, #'s 161-163, remained in service until mechanical failures, electrical failures, or structural deterioration caused them to be retired. Car #163 was retired after an electrical fire in 1988. Car #161 was retired sometime between 1988 and February, 1990. Car #162, still painted in the traditional red and cream colors, was the last Strafford car in revenue service, finally being retired due to electrical problems and roof deterioration on 3/30/90. With the retirement of #162, over 62 years of service from these vehicles on the P&W and its successors came to a close. Following their retirement from SEPTA, some cars escaped the scrapper's torch. Car #161 gained fame by operating across the Keokuk dam in Keokuk, Iowa during the Midwest floods of 1993. It and car #168 were later sold to the New York Museum of Transportation. Car #164 was later sold to the East Troy Electric Railroad where it is undergoing restoration. Cars #163 and 165 were rebuilt into gas-mechanical cars and operated in Mt. Dora, Florida, and El Reno, Oklahoma, respectively. Car #162 was sold to the Rockhill Trolley Museum in Rockhill Furnace, Pennsylvania and today is only survivor of the fleet preserved as a modernized 160 series car. The Strafford cars of the Philadelphia and Western Railway and its successors operated for over 62 years in the western suburbs of Philadelphia. They were among the oldest interurban cars still in service in the United States when they were retired and today some still carry passengers in diverse locations across the nation. |

![]()